Integrating Google Cloud Print into iOS

Setting up my family’s Chromebox was easy, until someone needed to print something. Google decided that in Chrome OS, the only method for printing should be through its Cloud Print service. Google Cloud Print is a service that provides a API for printing, both to send print jobs and to receive them. This is an example of forward thinking by Google, and greatly simplifies the experience in Chrome OS. However, this adds complexity for the consumer. I ended up configuring the printer in my house using an open source bridge running on a Linux server. Once I configured it properly, I began to really appreciate the advantages of Cloud Print. I enjoyed being able to print documents to my physical printer, and PDF files to my Google Drive, from anywhere in the world. Being able to print directly from Gmail is also awesome. However, I missed these luxuries on the device that I use the most, my iPhone.

Beginning with iOS 4.2, Apple introduced AirPrint as a method to print over the local network. Since then, Apple’s core applications, and many others, have added print functionality. I wanted to be able to print natively on iOS, but using Google’s Cloud Print service. The problem is, as Marco Arment writes, Apple is in the business of saying “no”. No to customizing the interface, and no to modifying the operating system. This is what I consider the biggest advantage of jailbreaking. Jailbreaking gives you the ability to sidestep Apple, and say “yes”. Not only this, but developing software for jailbroken devices, in the form of “tweaks”, proves to be a fun challenge. This is an account of how I integrated Google Cloud Print into Apple’s existing AirPrint functionality.

Building The Client

The first step to integrate Google Cloud Print into iOS was to implement a client. Google documents the Cloud Print API on their website, so the only thing that I needed to do was write a client for it. There are many ways to approach this, but I wanted to try something I have not tried before. I decided to delve into Core Data with Mattt Thompson’s AFIncrementalStore. AFIncrementalStore is a relatively new project, with the ambitious goal of mapping Core Data to a RESTful web service. I created a data model with Job and Printer entities, and implemented an AFRESTClient subclass to interact with the API. AFIncrementalStore is intended to be transparent, so I need only execute standard Core Data calls to use it. To fetch a list of all printers in alphabetical order, I can execute a standard NSFetchRequest:

1

2

3

NSFetchRequest *fetchRequest = [NSFetchRequest fetchRequestWithEntityName:@"Printer"];

fetchRequest.sortDescriptors = @[ [NSSortDescriptor sortDescriptorWithKey:@"name" ascending:YES] ];

NSArray *printers = [context executeFetchRequest:request error:nil];

To send a job to a given printer, I can insert a new Job entity into the context, and a request will be fired off in the background, transparently. Here is an example of sending a job to a printer:

1

2

3

4

5

6

CPJob *job = [NSEntityDescription insertNewObjectForEntityForName:@"Job" inManagedObjectContext:context];

job.title = @"TestJob";

job.printer = printer;

job.fileData = [NSData dataWithContentsOfFile:filePath];

job.contentType = @"application/pdf";

[context save:nil];

It is pretty cool to not have to interact with the network layer to use a RESTful API. For my purposes, I have found this approach to be great, but Core Data is not for everything or everyone. It is general knowledge among iPhone developers that Core Data is difficult to get right, and that when things do go wrong, they go horribly wrong. In this project, there are relatively few objects in the store, and the relationships between them are simple. I have yet to come across a serious problem (knocks on wood).

In addition to interacting with the Cloud Print API, the client also needed to authenticate using OAuth2. There are many implementations of OAuth2 on iOS, but I was attracted to AFOAuth2Client in particular, because it is based on AFNetworking, just as AFIncrementalStore is. However, AFOAuth2Client in its current state is terribly outdated and feature incomplete. This led me to give it an overhaul to better conform to the OAuth2 spec, and to add some features. One feature I added was the ability to easily store tokens in the keychain for safe storage.

Diving Into PrintKit

In order to integrate Google Cloud Print into iOS, it was integral to understand how Apple approaches the problem of printing on iOS. All of Apple’s magic lies in a private framework on iOS named PrintKit.framework. To understand this magic, I conducted static and dynamic analysis. For disassembly and static analysis, I have a copy of IDA Starter, which is considered to be the standard in static analysis. I also use class-dump, which parses the Objective-C metadata in a binary, and uses the data to generate readable class definitions. For dynamic analysis, I use Jay Freeman’s cycript, pronounced “sscript”, a hybrid between JavaScript and Objective-C. The interpeter can inject into a running process and provide a shell to do just about anything you want.

From analyzing PrintKit, I determined a few useful pieces of information. PrintKit has two components, the framework itself and its associated daemon. The first component, the framework, is relatively small with only six classes. Each class is a wrapper over a portion of the CUPS API, which is compiled into the framework. You can see this for yourself by looking at the symbols in the framework (you must run this on OS X with the iOS SDK installed in order for it to work):

1

2

$ nm $(xcode-select --print-path)/Platforms/iPhoneOS.platform/Developer/SDKs/iPhoneOS6.0.sdk/System/Library/PrivateFrameworks/PrintKit.framework/PrintKit | grep -c cups

328

The second component, the daemon, is known as printd. It is configured with launchd to listen over a UNIX socket. printd is actually a modified version of the CUPS daemon. This can be seen from its usage page (you must run this on a jailbroken iPhone in order for it to work):

1

2

3

4

# /System/Library/PrivateFrameworks/PrintKit.framework/printd -h

CUPS v1.5.0

Copyright 2008-2010 by Apple Inc. All rights reserved.

...

The framework and daemon communicate over the UNIX socket the same way they would normally be communicating over port 631. The daemon is started on demand, meaning it is only running when it needs to be.

However, in integrating Google Cloud Print, the daemon is of little importance. The proper layer to inject into and modify is the Objective-C layer, the six classes that serve as the API to the framework. Of these six, three are of particular interest: PKPrinterBrowser, PKPrinter and PKJob. The first, PKPrinterBrowser, functions as its name suggests. It browses for printers using Bonjour. Here is the header for PKPrinterBrowser, abridged to only show the parts we might care about:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

@protocol PKPrinterBrowserDelegate

-(void)addPrinter:(PKPrinter *)printer moreComing:(BOOL)coming;

-(void)removePrinter:(PKPrinter *)printer moreGoing:(BOOL)going;

@end

@interface PKPrinterBrowser : NSObject

@property (strong, nonatomic) NSMutableDictionary* printers;

+ (id)browserWithDelegate:(id<PKPrinterBrowserDelegate>)delegate;

- (id)initWithDelegate:(id<PKPrinterBrowserDelegate>)delegate;

@end

Each browser has a printers property, which contains the printers, and a delegate property, which wants to be notified of any changes. A browser object is created when you browse for nearby printers in the AirPrint dialog. The remaining two classes, PKPrinter and PKJob are model objects describing printers and jobs, respectively. Additionally, PKPrinter has methods for submitting jobs.

Putting It All Together

After implementing the Cloud Print client and thoroughly investigating PrintKit, I was now able to work on integrating the two. This was the most challenging part, but also the most fun. This is the point where the code entered the bounds prohibited by Apple. The code written prior, the API client, is independent and can be used anywhere. For example, I wrote an application using the API client for debugging purposes.

For those unfamiliar with jailbreaking, the piece of software that enables one to cleanly modify existing software is CydiaSubstrate. CydiaSubstrate is similar to SIMBL (which dates back to 2003) in principle, but has a more robust implementation. On a jailbroken iOS device, CydiaSubstrate is loaded into every process spawned by launchd. Once loaded into a process, CydiaSubstrate checks a directory for user-installed libraries, called tweaks, and selectively loads them into the process. Once loaded into the process, these libraries can then modify existing functionality.

As I mentioned earlier, the Objective-C layer of PrintKit is the best place to make modifications. It is low enough of a level where I would not need to modify any interface code, but high enough of a level so as to avoid the CUPS API. One of the goals is to display Google Cloud Print printers to the user. To do this, I can insert custom printer objects into PrintKit that represent printers in Google Cloud Print. PKPrinter objects are normally created by PKPrinterBrowser, so this seems like the logical place to insert them. Other objects see which printers PKPrinterBrowser has found by checking its printers property. Thus, if I was to modify the getter of this property, other objects would see my modifications. The advantage of only modifying the getter is that the modifications do not interfere with the internal state of the object, as the instance variable containing the printers is not modified. Here is some code from the project doing just this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

%hook PKPrinterBrowser

- (NSMutableDictionary *)printers {

NSMutableDictionary *orig = %orig();

NSMutableDictionary *combined = [NSMutableDictionary dictionaryWithDictionary:orig];

[combined addEntriesFromDictionary:thePrinters]; // Printers from somewhere

return combined;

}

%end

Now, if you are familiar with Objective-C, you are probably wondering about some of the funky syntax above: %hook, %orig(), and %end. The code above is written for something called Logos. Logos is a preprocessor, written in Perl, developed by Dustin Howett. What Logos does is it takes the code above, and translates it into Objective-C runtime calls to “hook” that method. It replaces the implementation of the method with a custom one, and makes the original implementation available with the %orig() macro. Here is the above example, ran through Logos, and made human readable:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

static NSMutableDictionary * (*originalImplementation)(PKPrinterBrowser*, SEL);

static NSMutableDictionary *replacedImplementation(PKPrinterBrowser* self, SEL _cmd) {

NSMutableDictionary *orig = originalImplementation(self, _cmd);

NSMutableDictionary *combined = [NSMutableDictionary dictionaryWithDictionary:orig];

[combined addEntriesFromDictionary:thePrinters]; // Printers from somewhere

return combined;

}

static __attribute__((constructor)) void initializeHooks() {

Class _class = objc_getClass("PKPrinterBrowser");

Method _method = class_getInstanceMethod(_class, @selector(printers));

IMP superImplementation = class_getMethodImplementation(class_getSuperclass(_class), @selector(printers));

if (_method) {

originalImplementation = superImplementation;

if (!class_addMethod(_class, @selector(printers), (IMP)&replacedImplementation, method_getTypeEncoding(_method))) {

originalImplementation = method_setImplementation(_method, (IMP)&replacedImplementation);

}

}

}

As you can see, the first example is orders of magnitude cleaner and easier to maintain than the second. This is why Logos is so incredibly useful for writing hooks. It makes writing hooks almost natural, and removes the need to muck around in the runtime manually and repetitively. This approach of directly replacing implementations is somewhat similar to method ‘swizzling’ that many Cocoa developers are familiar with. One of the key differences between swizzling and directly replacing the implementation is that swizzling involves adding a method to a class via a category. This can only be done when the target class is directly linkable, which is not always the case. Mike Ash wrote a great article outlining both of these methods.

But back to adding printers. Now that I am able to insert custom printer objects, I need to get these printer objects from the cloud to instances of PKPrinterBrowser. This is where the API client comes in. I can simply insert the API client into my tweak, and use it to fetch the printer objects. However, it is not that simple. There are many problems with doing this. The first is that a client would be created for every single application that invokes a print dialog. This is horribly inefficient. The second is that the copies of AFIncrementalStore and AFNetworking within my tweak would clash with the copies in any process that also uses these libraries, and lead to undefined behavior. This is very unstable. Both of these problems can be solved by moving the client out of the tweak, and into its own daemon. Within a daemon, nothing would clash, and there would only be a single client running at once.

The tweak could then communicate with the daemon, and ask it for printer objects. Beginning with OS X Lion and iOS 5, Apple added the XPC Services API. XPC stands for cross process communication, and it is designed to facilitate communication between daemons, or services, and other code. Beginning with OS X Mountain Lion and iOS 6, Apple added the NSXPCConnection API, which is an Objective-C wrapper built on top of the C API. On iOS, both XPC APIs are currently private, but they are exactly the same as on OS X. This means that the documentation is also the same.

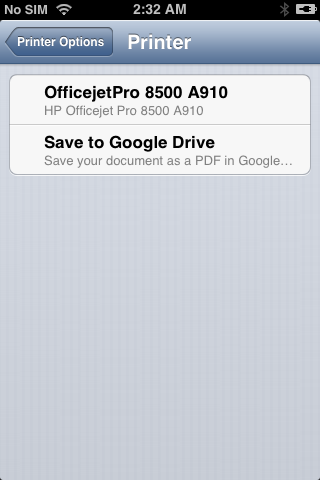

I went ahead and added the API client to a daemon. I further modified the PKPrinterBrowser class so that each instance opens a connection to the daemon and retrieves printer objects from it. I chose to use the NSXPCConnection API for convenience. Sadly, this forces me to drop iOS 5 support in my project. One thing I had to do in order to get this approach to work was convert the printer objects from NSManagedObject subclasses into PKPrinter subclasses, so they were compatible with PKPrinterBrowser and independent of the Core Data store. Here is a screenshot of the whole thing in action, working:

I also wrote a preference bundle that allows a user to authenticate using OAuth2 from within the iOS Settings application. The entire project is built using Theos, which is a makefile based build system written by Dustin Howett that eliminates many of the headaches that come with using makefiles. Theos was made expressly for the purpose of compiling projects for jailbroken iOS devices, and has many conveniences. Theos includes the ability to automagically preproccess files using Logos. It also includes support for building Debian packages, because APT is the package manager used on all jailbroken iOS devices.

So What?

While the tweak does not support sending print jobs yet, I have made the project open source under the MIT license for those who want to look through the code, play around with it, or even use parts of it. I do intend to eventually finish it and release it. I set out to integrate Google Cloud Print and iOS in the best way possible and the resulting project came out great. On top of this, I learned a whole lot in the process of building it.

I wanted to write this post to demonstrate a few things. First, that by jailbreaking, the possibilities are endless. Not as a user, but as a developer. Nothing in the userland is off limits, and everything is modifiable. In very few places in the mobile ecosystem is this offered. Android certainly has more freedom with their SDK, but there are still certain things off limits. Even when rooted, Java is a static language, making modification of other software difficult. The same goes for almost every other mobile operating system. The only exception I know of is WebOS because it is open by default, and a lot of it is written in JavaScript. Modification via patches is easy.

The second point I wanted to illustrate is that developing software outside of the sandbox makes you a better iOS developer. I am not saying that those who develop outside of the sandbox are better than those who develop within. Software written for the sandbox is certainly more important, as it impacts a much larger market. What I am saying is that developing software outside of the sandbox is a constant challenge, and you will certainly learn a few things by trying it. I am a strong believer in the idea that you must take something apart to understand how it works. A great way of doing this is by disecting iOS and writing software to co-exist with it. Developing software for jailbroken devices transformed me from an Xcode kiddy into what I am today. I now have a thorough understanding of the Objective-C runtime, reverse engineering, dynamic libraries, et cetera.

Lastly, developing tweaks is just plain fun. I have seen many people exercise their design talent once in a while and create an iOS concept video. While it looks great on video, how awesome would it be to actually create it and try it out? Tweaks do not necessarily have to be big, either. They can be as small as adding seconds to the lockscreen clock. Here are some great examples of small and simple tweaks. Developing for jailbroken devices can be a fun and challenging hobby, so I encourage other iOS developers to jump right in and give it a try!

Feel free to follow me on Twitter or check out my software. Additionally, if your company is hiring mobile dev interns this upcoming summer, and has no problem hiring a high school student, be sure to get in touch.

Discuss on Hacker News here.